Tuesday, February 3, 2026

How to Price an Audio Plugin - More Approaches, More Factors

James Russell

Music Software Marketing Consultant

James is a business and marketing consultant for music software companies. He's always on the lookout for new startups with the next big thing.

https://www.eggaudio.com/

At ADC24, I gave a talk on How to Price an Audio Plugin. The format of doing an 18-minute talk is as limiting as any fixed format: there’s a time limit, you have to explain everything with speech, and you have to give in your slides two weeks before the day. Naturally, there were some things I had to leave out.

With this article, I’m aiming to go deeper where the subject deserves it, mention the previously unmentioned, and add some changes to my thinking that have happened since then. This article can supplement the talk (below), or can stand alone completely.

Recapping the Basics – Pricing Digital Products

Digital goods aren’t like physical goods. After a plugin has been developed, which of course takes time and/or money, each license doesn’t bear any more cost to ‘produce’. This except for transaction fees, license fees (iLok, Native Access…), which mean there are some associated costs with each sale. This factor about selling digital goods can make it feel like any sale is profit, whether the buyer is paying $200 or $12.

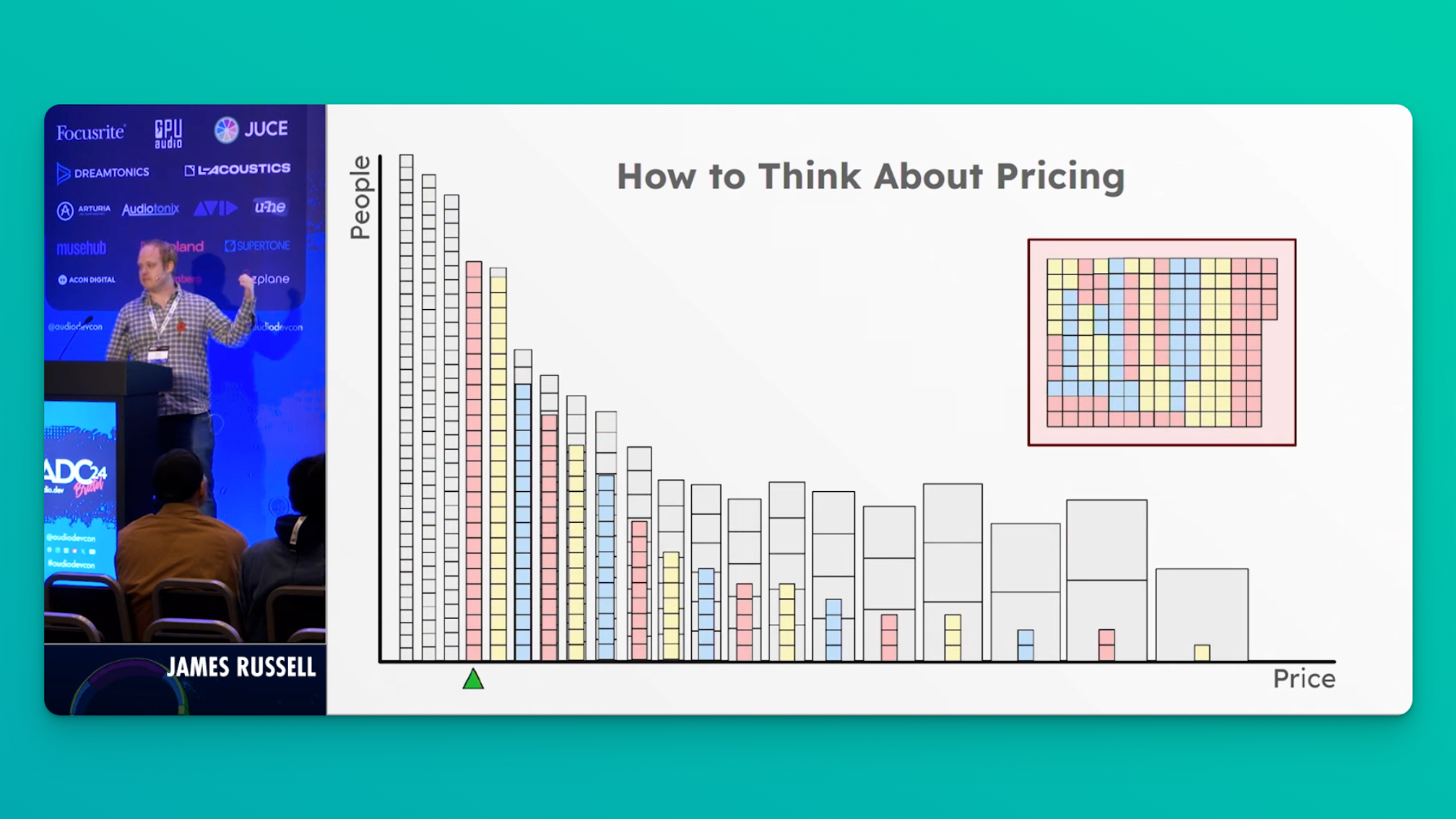

Assuming that you only set one price point for your product (which isn’t really true if you use discounts or coupons), then you can assume that at any given lower price point, there will be more people willing to buy the product than at a given higher price point. Every buyer has a price above which they won’t go.

The figure you might wish to maximize is orders*price (let’s call it OP). If setting the price at, say, $40 gets you 1000 orders (OP = £40,000); and setting the price at $25 gets you 2240 orders (OP = $56,000), then your OP-maximizing price point out of those two would be $25.

The sticky wicket: this is a massively simplified way to think of things. It helps you grasp what the game is and how you should be thinking, but it suffers from the following huge problems…

Problems with Thinking Using Orders*Price Maximization

- You can’t actually try out every single price point to see which one maximizes OP

- Setting a lower price point will devalue your plugin in people’s perceptions

- Plugins tend to have multiple prices anyway, as we’ll discuss later.

You shouldn’t just pick a number and hope for the best OP, but you can make some inferences from looking at the market in general, hoping to calibrate price points.

What the Buyer is Willing To Pay

Different buyers are “willing to pay” different prices for the same thing, and perhaps the end goal of any pricing model is to get closest to the price that each customer is willing to pay.

Travel is a good example. Everyone flying on a plane is getting the same result – they’re getting from Point A to Point B. But there are huge differences in the ticket prices paid throughout the flight. Whether it’s down to business class or economy class tickets, or simply down to the time at which the ticket was bought, two different people on the same plane could have paid radically different prices. Why? Because they were each willing to pay different prices. For a video that sums it up well, this example demonstrates how prices work in general.

When a modern-day company experiments with a shady price strategy such as InstaCart charging different prices to different people; or even a groovy pricing strategy such as plugin companies charging different prices in different countries with different purchasing power; there’s a logical thought behind it: different people are willing to pay different amounts.

I’ve come to believe that The Buyer Sets the Price, and this is the reason.

Different Prices in Different Territories?

By the way, Moonbase are close to launching a feature that lets you charge a different price to customers in different locations, and to make it far less of a headache than implementing that system yourself. It lets you balance your price point with the country’s purchasing power. With more prices for more people, more people will be willing to pay based on their local standards.

Check out the Moonbase roadmap item: Pricing based on Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)

Adding Discounts into the Equation

Let’s say that you choose a main, ‘MSRP’ price point, and a standard discounted price point, and stick to both of those, without any variations. Thinking rationally, (which isn’t always a good idea), you would expect that…

- Potential buyers who are willing to pay more will buy the plugin at its higher price

- Those not willing to pay as much (can’t afford it, don’t consider it worth it) will wait until it reaches its lower price.

In theory, this means that you get to select two equilibrium price points, and get the best of both worlds. You get the more luxury price from those who are willing to pay it, but you don’t lose out on those who are only willing to pay less. Not everyone values the same digital good by the same amount.

In practice, though, the result can be quite different: most buyers end up waiting and paying the lowest price. Even if they can afford the higher price, many join the mailing list, waiting for the inevitable “Sale Ends Tuesday” email. Some may use price alerts from a site like Music Software Deals. In the end, and as a result, many developers find that most of their sales come from discount periods, with a small amount of revenue coming from regular-priced periods – although not all developers I’ve worked with experience this effect.

This is often beyond a single brand’s control, too. The majority of the music software industry uses discounts as a pricing strategy, and customers have learnt to expect them. Developers who price deceptively, with heavy discounts such as $299 down to $29, have in particular led people to expect reductions.

If done wrong, then, discounting price strategies can devalue the product in the eyes of the customer, and discounts can end up as the de facto actual price. They even reduce the perceived value of other developer’s software. As the consequences are felt around the whole industry, we end up with the well-known “race to the bottom”.

Oh well. Here are the factors that affect pricing of a plugin, and why.

Key Main Factors that Affect Audio Plugin Pricing

These three things seem to have the most effect on setting prices, from what I can tell.

Competitor Pricing

This is probably the most important factor influencing plugin pricing. Most people know that, before buying something, it’s worth shopping around. You’d compare the prices of two hammers or two corkscrews, so why won’t your customers compare two EQs or two reverbs?

This isn’t to say that you should price cheaper than your competitors or even within their range, but that you’d be foolish to not even know what was being charged for similar offerings, smaller offerings or larger offerings.

Uniqueness of Offering

If you’ve made something that can’t be found anywhere else, you can usually justify charging more for it. If you hit upon a good new idea, then you can be sure that competitors are on the way to copy it.

If you’ve hit upon a very esoteric plugin that solves the highly specific problems of a small group of people (an obscurity within a niche within a specialty), then these people are probably willing to pay more to get it. The small audience may be compensation for the fact that you’re less likely to be copied.

Under-Milestone Pricing

Annoyingly, I’ve come to believe that $49 is quite a lot more effective a price point than $51. I wish it wasn’t but I’m quite sure it is. The same is true for $99, and of course, everyone’s favourite, $29. Sorry everyone.

But it’s also interesting to note that, when selling in different currencies, which you should, these exact figures can vary. The fact that the buyer sets the price is a good argument for pricing specifically in different currencies, getting under the milestones every time.

Some Secondary Factors that Affect Pricing

These factors should influence a pricing decision, but may be harder to define, or may apply differently.

Market Leadership

If you’re the market leader in a certain area, you’ll probably know it. Being the leader doesn’t always mean you have the best product (however you define ‘best’), but it gives you a good justification to price higher than your competitors, making the others compete on value rather than reputation.

Professionals vs Hobbyists

This factor gets murkier the longer you look at it. In principle, on average, a professional will pay more for a tool than a hobbyist. For professionals, there’s more on the line, there’s a clear addition of value for a tool being used to make money, and there’s often someone else paying the bill.

On the other hand, many professionals will be just as inclined to wait for sale pricing as any hobbyist, and there seem to be fewer professionals to begin with.

How to Think About Pricing Your Own Plugin

After a wash of abstract ideas and examples, here are a few concrete steps you can take to assess how much to charge for your own plugin.

Evaluate Competitors

Gather plugins that offer similar solutions to yours. KVR Audio is a useful place to start, and LLMs can sometimes help with vaguer search queries. Plot their prices, and check for historic deal or sale pricing if you can.

You may not feel that other plugins provide the exact same functionality as yours. Others may do so as part of a larger package. Not every plugin provides a concrete solution to a specific problem, but there are usually similarities to be found – even if it’s just current workarounds.

View the Landscape Like a Potential Customer

Try to view your market as a potential customer and see what they will find. When searching for a solution like yours on Google, what comes up?

Which competitors that you found in the previous step are actually visible to potential customers? Sometimes a plugin can prevent itself from being found just by being poorly named, for example.

Situate your Price within the Landscape at a Point that Reflects Features

Let’s say one competitor has a simple solution for $30, and one competitor has a very specific solution for $70…

- If you have a feature set in between those two, be the price point in between ($50).

- If you have an overly complicated solution, make a move for the highest price

- If you have a super-simple version of the solution, set your price to $29. Anyone wanting just that function from your $30 competitor will have a slightly better option.

Consider the Power of your Competition

Up against a company with a million-strong mailing list, or powerful SEO for plugins, or a huge social media following? You may have to compete on price – even if your feature set is bigger than your juggernaut competitor’s.

Then again, I’ve helped a few people use the power of a huge competitor against them, and I’ve helped clients realize that when a massive company launches a similar plugin, it might not be so bad for business.

How’s Your Ability to Get Attention?

If you have a mouthpiece – an existing customer-base or fan-base of music producers (no, not just music listeners), then you can likely push the price higher. Anyone doing a free plugin intro strategy can count a larger audience to promote the full version to.

Doing Sales?

If you’ve chosen to go with a discount strategy, your multiple prices should land at different points along your price/feature-set plot of competitors. Take into account your competitors’ sale prices too.

Frankly, the most common way to do this is for a developer to set a preferred price as the discount price, and inflate it to reach their main price (MSRP). This is usually done by a developer who expects that sales will only happen when the plugin reaches that genuine, discounted price point.

Not Doing Sales? How Long are you Willing to Wait?

It can take months or years to build a reputation while holding steady on a single price. Consider your general financial situation, whether you can survive the short term in favour of the long term, and increase your price if you have the time or patience to build a more loyal fan-base over a longer time.

Drop Below Milestones

Have you reached the scientifically curated price tag of $63? Just drop it to $59.

Even $59 should probably be dropped to $49. I’ve seen a lot of examples that have led me to take this annoying fact more seriously.

Consider the different currencies your plugin is available in, and the taxes that different territories will experience. You may feel you’ve crossed a milestone by setting your price to £49, but if a customer sees $56 on their end, or in their checkout, it could be a significant put-off.

Ask Me What I Think

For a one-on-one session on pricing, launch strategy or an evaluation of your current plans, you can find me and more about my work at eggaudio.com.

Start selling through Moonbase

Sign up today to get started selling your software through Moonbase.